Wild tulips are threatened by many localised activities such as livestock overgrazing, mining, urbanisation, and opportunistic collection of flowers and bulbs. These are currently damaging specific populations and causing numbers of individuals to decline. Yet what if there was a threat that occurred across the whole distribution of tulips? What if there was something that could affect every single tulip? Well, climate change is something that could do this as it alters temperature, rainfall, and seasonality patterns globally, which in turn influence both the growth and reproduction of the world’s plants, including wild tulips. With the release of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) latest report, we know that climate change is happening and at an extremely worrying rate. However, no research had been done to examine the impact of climate change on wild tulips until we decided to carry out this important task and recently, we have published our results from this endeavour in the journal Biodiversity and Conservation (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10531-021-02165-z).

You may be wondering “how can you understand a threat that will change going into the future?”. Well, one common way to do this is to use current data alongside predicted environmental conditions to model, and therefore predict the impact on future species’ distributions. This was the avenue we chose. To start with we gathered distribution data for around 25 tulip species across the Central Asia region, including important new data that we collected during our fieldwork expeditions. Unfortunately, even with our new data, many species had too few data to be modelled so we had to carefully select taxa that were likely to give results that would be both reliable and accurate. Once this was done, we downloaded climate data from the WorldClim database, a free to access record of 19 bioclimatic variables based on annual rainfall and temperature patterns. These variables capture both present day environmental conditions and conditions under future predicted climate scenarios.

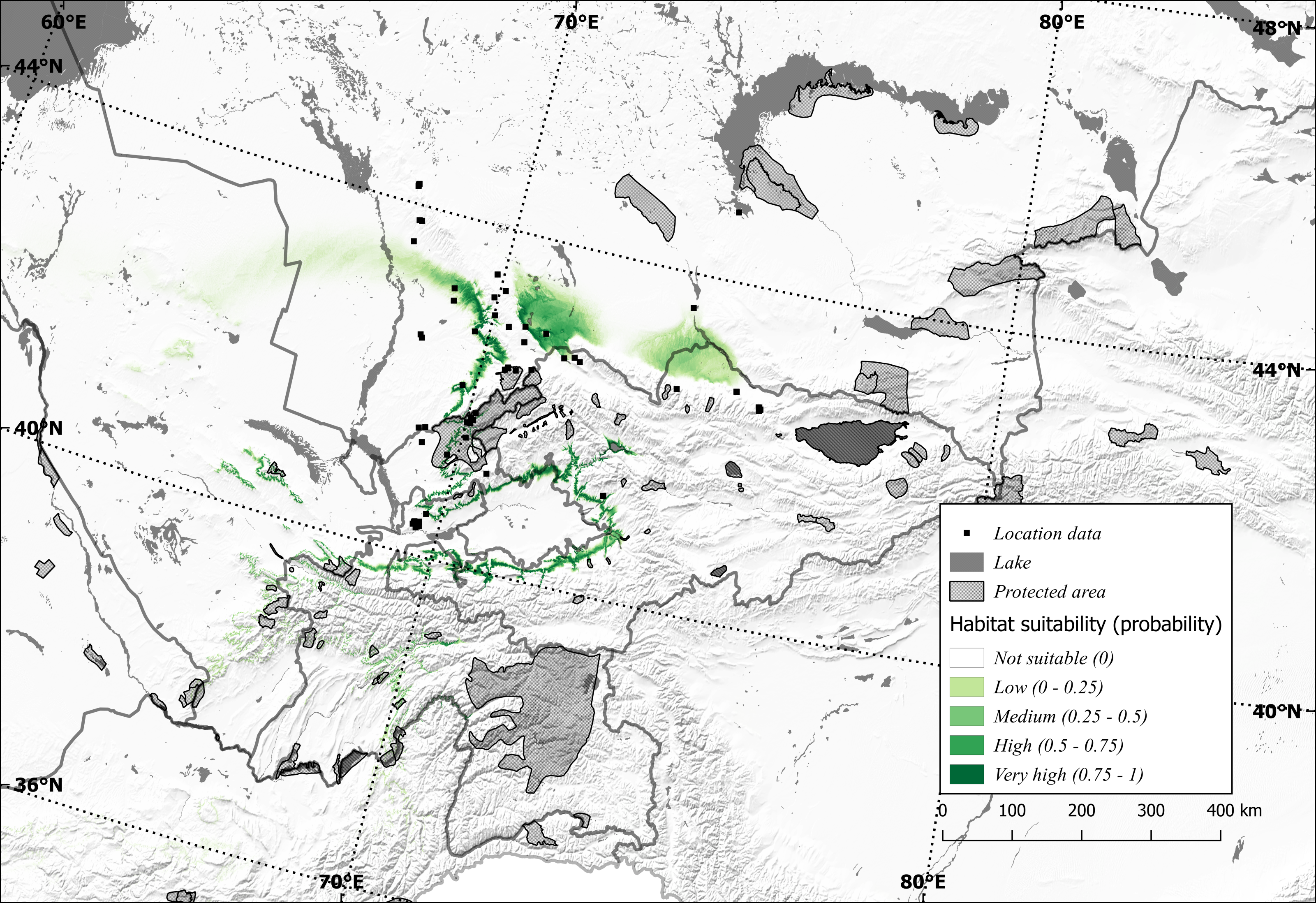

Putting both the distribution data and environmental data into the widely used modelling software (MaxEnt), we developed maps of species’ present-day distributions as well as those for the years 2050 and 2070. This software uses a maximum entropy approach to predict the distribution of a species based on the current known locations of a species and the environmental conditions that occur in these areas. This was the first ever piece of research that explored tulip distributions across the entire Central Asia region rather than just within a single country, making it extremely useful for understanding the broad scale impacts of climate change. Having regional distribution maps for both the present day and future climate change scenarios allowed us to explore how the distribution of each species might alter as climate change progressed, how protected area coverage for species was predicted to change over time and also how a regional level perspective on extinction risk compared to a country level view.

Our results were both surprising and depressing. Overall, we modelled ten species, one representing a relatively recently described species with little data and nine taxa with good quality data. As expected, modelling species with little data was shown to be not very useful and this is worrying because there are many newly described species in the region that are data deficient. There is therefore an urgent need to gather more data for the many tulip species in Central Asia. However, we observed informative results from the other nine species we had modelled. Of these nine only four were predicted to have any suitable habitat remaining under the climate change scenarios we applied and even these were in drastically reduced areas. This held for both a scenario where CO2 emissions carried on at their current rate and also for one where CO2 emissions stopped completely. Clearly, climate change is going to have drastic negative impacts on wild tulip species. This will be exacerbated as we see that protected area coverage, which is already fairly limited for most species at present, would decrease heading into the future. In addition, future suitable habitat is likely to be at higher altitudes causing species to die out if they are unable to migrate resulting in greater fragmentation of populations.

Many of these species occur in multiple countries and interestingly during our research we noted differences between national species’ extinction risks and the global extinction risk assessment. This means that if we want to protect and really understand these species, a regional community that works more closely together will need to be encouraged. Fortunately, we are well on the way to facilitating this with further collaborations in Uzbekistan formalised and connections in Kazakhstan now starting to take shape. With a common goal for regional conservation activity tulips will have a better outlook.

So, what does this all mean? Well, it means that tulips are not only facing localised threats but will also struggle in the face of climate change. In turn this means there is certainly a need for collaboration across the region of Central Asia, a rethink of how tulips can be better represented in protected areas, as well as renewed efforts to fortify and protect current populations and expand ex-situ collections. Although the results seem extremely negative, modelling simplifies the true picture and tulips may be more resilient than we think. Small patches of habitat may remain in the current distribution, tulips may be able to adapt and, in some circumstances, migrate to new areas. So, all is not lost!

However along with the IPCC’s report confirming climate change’s drastic impacts and our research so far, there is certainly a lot of work still to be undertaken to protect not only our wild tulip populations but flora and fauna in general.

It’s not just tulips that are under threat from climate change. Many plants face an uncertain future under even the most optimistic climate change predictions. The pace of change is such that most plants will not be able to adapt quickly enough so our efforts in ex situ conservation are even more urgent. Seed banking and growing genetically diverse plants as part of conservation collections in botanic gardens allows us to conserve species and retain future options for reintroduction, assisted migration and other in situ techniques which we will have to employ to maintain the world’s plant diversity, and to continue to benefit from the many services plants provide us all with.

Dr. Colin Clubbe (Head of Conservation at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew)